The blame for me becoming an insufferable nuisance to the teachers at Glenfield College in 1980 can't be laid entirely at the feet of the Texas Instruments corporation. The setup for that was laid down rather earlier, thanks to the writing of one of the world's great educators: Martin Gardner, who was to mathematics what the great Sir David Attenborough is to naturalists.

When my parents divorced in 1976 I chose to live with my father, who continued to work, thus leaving me a lot of time alone. A great deal of that free time was spent with a pile of back issues of Scientific American which he had subscribed to in the mid-60s when he was a young man - before the unplanned arrival of myself thoroughly derailed his life in 1967.

When my parents divorced in 1976 I chose to live with my father, who continued to work, thus leaving me a lot of time alone. A great deal of that free time was spent with a pile of back issues of Scientific American which he had subscribed to in the mid-60s when he was a young man - before the unplanned arrival of myself thoroughly derailed his life in 1967.Scientific American was a great magazine for a 10-year-old boy; articles written by eminent scientists, but carefully targeting a reading age of (I'd guess) about 14 it did a fantastic job of explaining science clearly, but without sacrificing too much to make it truly "popular" in the oversimplified way that is more common nowadays (with, say, the Discovery Channel).

And as great as every issue was, the very best part of all lurked at the back (just before "The Amateur Scientist" column), in the form of the "Mathematical Games" column in which Martin Gardner regularly served up an essay devoted to recreational - but still quite serious - aspects of mathematics.

And as great as every issue was, the very best part of all lurked at the back (just before "The Amateur Scientist" column), in the form of the "Mathematical Games" column in which Martin Gardner regularly served up an essay devoted to recreational - but still quite serious - aspects of mathematics.From him I learned about counting on your fingers in Binary - spending hours counting up to 1023 and back down - and how the so-called "Russian Peasant" multiplication worked, which was a curiosity for decimal but was exactly how computer arithmetic worked. Or studying the Towers of Hanoi puzzle, the solution to which can again be understood based on the properties of numbers when represented as binary.

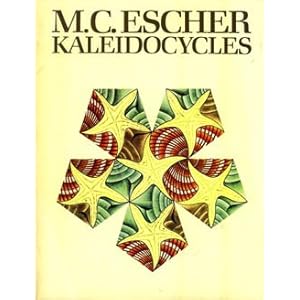

Of course those were the more serious articles but Martin Gardner's columns also included plenty of things which were nothing but sheer fun, and probably the greatest of these was Flexagons, from simple flats to the wonderful solid Tetrahexaflexagons. Just as I was getting fascinated by these a truly wonderful book was published, which my Father spent a horrendous amount of money to buy for me: M. C. Escher Kaleidocycles, because flexagons and the magnificent tiled drawings of Maurits Escher go together perfectly.

With that kind of early start, it's hard not to become math-obsessed, and since there weren't computers around to be used back in the late 70's I was absolutely primed to become completely fascinated by them when one finally came within reach. And indeed, that's probably why jumping into writing assembly language appeared to come so easily, because I'd years before then absorbed most of the fundamental prerequisites.

With that kind of early start, it's hard not to become math-obsessed, and since there weren't computers around to be used back in the late 70's I was absolutely primed to become completely fascinated by them when one finally came within reach. And indeed, that's probably why jumping into writing assembly language appeared to come so easily, because I'd years before then absorbed most of the fundamental prerequisites. These days perhaps it would be harder to get hooked on maths quite the same way, with so many distractions around - not just mobile telephones and the internet were yet to appear, but back then there was precious little worth watching on New Zealand's two television channels either (although to be fair we did get to see some superb BBC programming, from the classic Horizon documentaries to James Burke's incredible Connections TV series

These days perhaps it would be harder to get hooked on maths quite the same way, with so many distractions around - not just mobile telephones and the internet were yet to appear, but back then there was precious little worth watching on New Zealand's two television channels either (although to be fair we did get to see some superb BBC programming, from the classic Horizon documentaries to James Burke's incredible Connections TV seriesToday, all that raw information (and much more) is out there and in principle readily available, but it's mostly drowned out by a cacophony of ephemera. I can only hope that youngsters today are getting steered at this kind of material, and can draw from it a sense of the richness of the world and the power of science, and thus choose to embark on a career in science or engineering out of real passion.

No comments:

Post a Comment